The early years

The image of Hans Christian Andersen inevitably arises when picturing the young Carl Nielsen, even though sixty years separate them in time. Andersen became the world’s great storyteller and an internationally acclaimed writer, while Nielsen became Denmark’s most important composer and musical personality. But both came from a common background, both were born on Central Funen in the heart of Denmark, and both left for the capital of Copenhagen when they were teenagers, filled with the dream of becoming an artist.

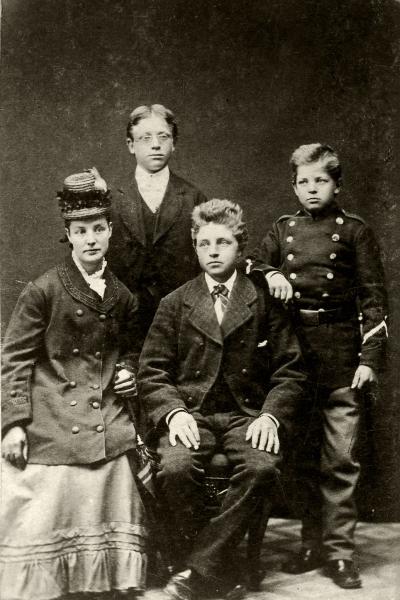

Nielsen was born into a large family of humble means on 9 June 1865. His father worked as a farm labourer, painter and musician, and his mother was musical as well. With much warmth, tenderness and literary skill, Nielsen depicts a childhood filled with impressions of nature and music in his delightful memoirs, My Childhood. When he was six years of age, his mother gave him a three-quarter-size violin, and as a fourteen-year-old he auditioned for a place in the military orchestra in Odense and was accepted. Here he played different brass instruments and took lessons in violin playing.

But poverty was a fact of life. One year after his 60th birthday, Nielsen told a newspaper that ‘I was paid three kroner and 45 øre every five days, plus a loaf of bread (…) This is how I lived for two and a half years, after which my salary increased a little, but I had to buy my own civilian clothes in order to be able to play at barn dances.’ But in his memoirs he recalls that ‘the extra income I sometimes made when I was allowed to play alongside my father at festivities in the country, I could partially put aside.’

For 50 kroner he was able to buy and old piano from a watchmaker, paying in partial instalments, and spending ‘all my free time at the piano.’ He bought sheet music, among them Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, and ‘it was like cutting into a mighty oak tree with a small penknife and never penetrating all the way through the bark. But now and then there were small glimpses when a pair of notes collided, affecting me altogether differently than any other music I knew. In stories about Indians I had read that the savages make fire by rubbing two pieces of wood against each other until they eventually began to glow (…) it kindled my own fire.’

It was like cutting into a mighty oak tree with a small penknife and never penetrating all the way through the bark. But now and then there were small glimpses when a pair of notes collided, affecting me altogether differently than any other music I knew.

When he was seventeen, Nielsen was promoted to corporal and may have thought his future to be secured. But at the same time he eagerly began to compose ‘without the slightest theoretical knowledge’ – dance music, music for marching band, and even a string quartet, ‘without any originality, but fresh and alive’. Wealthy and influential acquaintances – a merchant and a bicycle manufacturer in Odense and not least a powerful Danish politician from Funen – recognized his unusual abilities and encouraged him to pursue a professional music education.

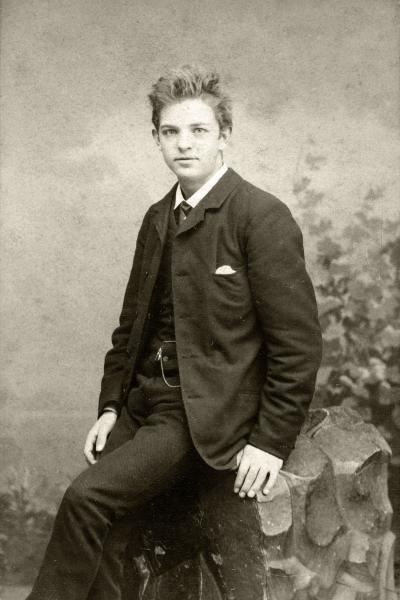

After auditioning in May 1883, he was offered a scholarship at the music conservatory, and in early January the following year, eighteen years old, he moved to the capital. During his studies he continued to receive financial backing from his benefactors, although the extent and regularity of these contributions are unknown. By the end of 1886 he managed to complete the three-year program and pass his exam as a violinist.

Nielsen’s early youth, like that of many other young people, was a period filled with ideas about the opposite sex. An exceptionally pensive passage at the end of My Childhood speaks of a time ‘that partly eludes my memory’, and he ponders ‘whether all the turmoil and commotion I experienced was beneficial or damaging to my professional and personal development.’ He writes about ‘the strangest, most misguided notions, also erotic ones’, about ‘phantoms from right and left, above and below’. And he acknowledges that ‘the most primitive sentiments of human nature’ involve the risk of ‘being bitten by the snake’. Read in the light of his readily ignited passions, his infidelity and marital crises, his statements appear like the continual musings of a 62-year-old man over an uncontrollable aspect of life.

A steamy, platonic infatuation with the fourteen-year-old daughter of a merchant from North Jutland gave rise to many silly but also thoughtful letters in the years following the conservatory, but to very little direct contact. The many romantic love letters to the distant beloved did not deter him from becoming involved in a number of less platonic escapades, however.

A steamy, platonic infatuation with the fourteen-year-old daughter of a merchant from North Jutland gave rise to many silly but also thoughtful letters in the years following the conservatory, but to very little direct contact. The many romantic love letters to the distant beloved did not deter him from becoming involved in a number of less platonic escapades, however.

In January 1888 he fathered a son with a housemaid his own age from Copenhagen, and that same autumn his conflicting feelings culminated in a substantial personal crisis that saw an end to the relationship with his betrothed from Jutland and brought him to the brink of suicide. As a matter of fact, sexuality forms the primary, demonic counterpoint to ‘high and pure art’, to love and ideals throughout Nielsen’s life.

In 1910, after nineteen years of marriage, his wife was unaware of yet another affair that in all likelihood made him a father once again. And the most profound crisis in his life was the fundamental loss of trust and intimacy in his relationship a few years later as a result of his incessant philandering. Not only did this lead to many years of separation, but also left Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen with a permanent wound that only began to heal some ten years before his death when they found back together again.

In a newspaper article from 1906, ‘Mozart and our time’, later published in conjunction with his 60th anniversary in the essay collection Living Music, he writes about Mozart that ‘he shall be forgiven for not being an angel, but a mere human being with human desires, hopes, cravings, passions, virtues and faults, and all the things that bring human beings far down and lift them high up.’ His own secret hope of forgiveness on similar terms can be glimpsed between the lines. His worst marital crisis yet had taken place the year before, and by all accounts it was at precisely that moment he initiated a long string of liaisons and affairs that was to continue for a number of years.

He shall be forgiven for not being an angel, but a mere human being with human desires, hopes, cravings, passions, virtues and faults, and all the things that bring human beings far down and lift them high up.

At the conservatory, the internationally renowned composer Niels W. Gade was both driving force and director, to the extent that one spoke of ‘Gade’s conservatory’. Nielsen developed a distantly cautious relationship to the mentor of Danish music, but in a letter to his fiancé in Jutland he describes Gade as ‘a great and original spirit, and exceptionally interesting.’ And upon learning of Gade’s death in 1890, he noted in his diary: ‘Empty and black! Terrible!’

His debut as a composer – two movements for string orchestra – took place in September 1887 at the Tivoli Concert Hall, and his first mature work, today known as Little Suite for Strings, was premiered here as well the following year. It is a unique, captivating and elegant opus 1, and was received with enthusiasm by the audience. The second movement – an interlude in waltz time – had to be repeated. The critics, too, were positive about the young composer ‘unknown to everyone’. But the great Niels W. Gade was reserved. ‘Young Nielsen,’ he is said to have commented, ‘you are messing about too much!’

In the early summer of 1889, a number of vacancies opened up in the Royal Orchestra’s string corps, and after a successful audition, Nielsen joined the second violin section, as was the custom for new members. But thanks to his growing reputation as a composer, not least after the first performance of Little Suite, he realized he had to escape Copenhagen’s narrow cultural environment in order to gain new impulses.

Dear God, what a giant of our time … a mighty genius (…) The musician who does not find Wagner great is himself very small.

The so-called ‘Ancker Grant’ (Det Anckerske Legat) allowed young artists of limited means the opportunity to experience the European art scene, and in February 1890 Nielsen managed to secure a scholarship in the amount of 1800 Danish kroner, the equivalent of an annual Royal Chapel salary with longer tenure than his (as a new member of the orchestra he only earned about 1200 kroner). He applied for leave of absence and, equipped with a recommendation by the highly esteemed Niels W. Gade, left in September to travel abroad, a journey that was to last for almost a year.

It was part dream journey, part educational trip. Denmark’s first gramophone was still ten years away, and many great musical works were practically unknown, even among musicians. In cities such as Dresden, Leipzig and Berlin, Nielsen met some of the most illustrious names in cultural life, attended countless concerts and wrote enthusiastically in his diary about German colleagues such as the world-renowned Johannes Brahms and Richard Strauss, only a year older than himself. The experience of hearing Richard Wagner’s entire Ring cycle in Dresden overwhelmed him: ‘Dear God, what a giant of our time … a mighty genius (…) The musician who does not find Wagner great is himself very small.’

In the spring of 1891, by now in Paris, he met the young Danish sculptor Anne Marie Brodersen and fell in love. Together they travelled on to Italy and married in May. A string quartet in F minor, written during the journey, was to be the first of Nielsen’s works to receive international attention the following year.

You would think that this score had fallen down from heaven.

After his leave of absence he resumed his post in the Royal Chapel Orchestra, but at the same time a symphony had begun to stir his imagination. He had studied Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony for years – ‘I can write it down from memory’ – and the first movement’s tight formal development, based on a brief motif, fascinated him in particular. ‘You would think that this score had fallen down from heaven,’ he noted in his diary in Berlin.

Nielsen’s own first symphony begins with a similarly distinctive motif, and experiments with both tonality and rhythm. The main key is G minor, but the finale ends in C major – along the way, the two keys even engage in a kind of duel – and the work opens quite untraditionally with a powerful C major chord. This tonal ambiguity, reminiscent of the old church modes, allows for lightning-fast shifts between major and minor, something that was to become a characteristic trait of Nielsen’s music. Also the use of syncopation and irregular accents were typical features, and a consummate sense of melody followed him throughout his life.

The symphony received an enthusiastic response at its presentation in March 1894, and the reviewers agreed that much could be expected of the composer in the future. The leading Danish newspaper Politiken even went so far as to claim that ‘to this day, none of our younger composers have written a significant piece of music such as this.’

The favourable reception of his early works naturally strengthened Nielsen’s confidence and motivated him to take another trip abroad in the autumn of 1894, now with a direct view to promoting his music. But the results failed to materialize. And during the following year, when he introduced a powerful, at times almost forced Symphonic Suite for solo piano, accompanied by the provocative Goethe quotation ‘Ah, the delicate hearts. Even a dabbler can stir them’, the critics were no longer gracious.

His first violin sonata in A major did not fare any better in January of 1895, as many felt the music to be strained and distorted, and one critic wrote that the dialogue between violin and piano almost seemed like ‘two warring parties flying at each others’ throats.’ But for Nielsen this was merely an expression of ‘infinite bullheadedness’, and in a letter to a colleague he emphasized: ‘I believe firmly and fully in my work.’

I believe firmly and fully in my work.

With Hymnus amoris for vocal soloists, chorus and orchestra, a hymn to love first performed in April 1897, Nielsen reached a preliminary artistic peak. He chose to have the Danish lyrics translated into Latin, because ‘this language is monumental and elevates you above perceptions that may be too lyrical or personal’, but having been acclaimed as the country’s young and brilliant talent a few years earlier, he was now faced with the ‘Law of Jante’, or ‘tall poppy syndrome’. A highly-regarded critic wrote: ‘Good grief – why does our little all-Danish Carl Nielsen, who only a few years ago still stood on Odense’s town square blowing his horn or beating a triangle, why does he now have to insist on conveying his feelings in Latin?’

Good grief – why does our little all-Danish Carl Nielsen, who only a few years ago still stood on Odense’s town square blowing his horn or beating a triangle, why does he now have to insist on conveying his feelings in Latin?

Nielsen’s next symphony, his second, was written in the years 1901–02 and was linked to a specific personal experience. The composer tells of a village inn where a naively coloured picture on the wall caught his attention. It was divided into four panels, each depicting one of the four temperaments. ‘I had laughed out loud and belittled these pictures, but my mind constantly returned to them (…) these crude pictures contained some type of seed or idea.’

I had laughed out loud and belittled these pictures, but my mind constantly returned to them (…) these crude pictures contained some type of seed or idea.

The notion of four different characters in four movements sounds more like a Baroque suite than a symphony – the essence of a symphonic work lies in its contrast, development and dynamic polarities, also within the individual movements. A temperament is a tendency, not a persistent psychological climate, but Nielsen was fully aware of this. The first movement’s irascible choleric clearly has his quiet moments in the second theme, the melancholic comes close to being bombastic and pathetic towards the end of the third movement, and the complacent optimist of the last movement becomes convincing thanks to a recurring, purely melancholic theme in the strings. In fact, all the movements incorporate aspects of all four temperaments, with the possible exception of the phlegmatic second movement.

On 1 December 1902 the symphony was introduced to the public. But by that time Nielsen had completed his most ambitious work so far, a full-length opera whose first performance had taken place at the Royal Theatre only three days earlier.

Translation by Thilo Reinhard